This story was funded by our members. Join Longreads and help us to support more writers.

Colin Dickey | Longreads | October 2019 | 14 minutes (3,729 words)

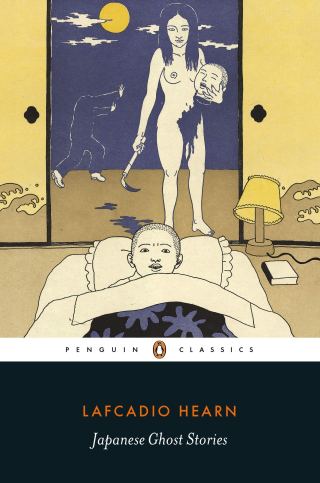

“The daimyō’s wife was dying, and knew that she was dying.” So begins Lafcadio Hearn’s uneasy and unsettling ghost story, “Ingwa-Banashi,” gathered first in his 1899 collection, In Ghostly Japan, and republished this year in a new Penguin Classics anthology edited by Paul Murray. As the daimyō explains to his wife that she is dying and preparing to leave “this burning-house of the world,” he offers her any final rites she may request. She asks him to summon one of his concubines, the nineteen year-old Yukiko, whom, she reminds him, she loves like a sister.

Yukiko arrives, and the dying woman tells her that one day she will rise in rank and be made the honored wife of the daimyō, a fortune that the low-born Yukiko cannot believe. As her last request, the daimyō’s wife asks Yukiko to carry her out to the courtyard to see a cherry tree in bloom — obligingly, Yukiko lowers her back and allows the old woman to wrap her arms around her, to carry her. Once she has grasped hold of Yukiko, though, the old woman laughs, clutches tight, and, with her dying breath tells Yukiko: “I have my wish for the cherry-bloom — but not the cherry-bloom of the garden! … I could not die before I got my wish. Now I have it! — oh, what a delight!”

Yukiko soon discovers that the woman’s corpse has somehow attached itself to her own body; doctors cannot pry it loose for fear of tearing Yukiko’s skin. They ultimately decide to cut it free, leaving only the corpse’s hands, which are cemented fast to young Yukiko’s breasts. “Withered and bloodless though they seemed, those hands were not dead. At intervals they would stir — stealthily, like great-grey spiders. And nightly thereafter — beginning always at the Hour of the Ox — they would clutch and compress and torture. Only at the Hour of the Tiger the pain would cease.”

“Ingwa-Banashi” is one of Hearn’s stranger tales, something that sticks with the reader long after you’ve put it down, fusing to your memory like a disembodied hand. It isn’t just the horrific state Yukiko is left in; it’s the baffling lack of any real reason offered. What accounts for Yukiko’s fate? She is a concubine, to be sure, but just one of many, and nothing in her personality singles her out for such treatment, nor does the story offer anything incriminating about her that might justify this monstrous calamity.

Hearn offers this in a footnote: “Ingwa is a Buddhist term for evil karma, or the evil consequences of faults committed in a former state of existence. Perhaps the curious title of the narrative is best explained by the Buddhist teaching that the dead have power to injure the living only in consequence of evil actions committed by their victims in some former life.” Whatever Yukiko’s crimes, they predate this life, and lie outside the borders of this short narrative. Nonetheless, she is bound to them and by them.

*

The stories in this new Penguin anthology (titled Japanese Ghost Stories) are why Hearn (who also went by the name Koizumi Yakumo) continues to have a lasting legacy in both America and in his adopted homeland, Japan. As Zack Davisson, author of Yurei: The Japanese Ghost, wrote, “When talking about yurei, all roads eventually lead to Lafcadio Hearn. In Japan, the two are almost synonymous. Say ‘yurei’ to a Japanese person, and the response is almost always ‘Lafcadio Hearn.’ Got to a bookstore in Japan, and ask the clerk for a book about yurei, and the first thing put into your hand will almost always be a copy of Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Any discussion of the history and cultural impact of Japanese ghosts would be incomplete without understanding the man who so diligently collected and published the mysterious legends with which he found himself surrounded.” As Davisson explained to me over email, “Hearn was instrumental in collecting and preserving Japanese folklore at a time when the Japanese government was actively attempting to eradicate superstition from the common people in favor of the new tools of science and industry.” Gathering up scraps and half-remembered tales, he forged them into an enduring corpus of eerie stories that have continue to linger.

Get the Longreads Top 5 Email

Kickstart your weekend by getting the week’s best reads, hand-picked and introduced by Longreads editors, delivered to your inbox every Friday morning.

Throughout his writing, Lafcadio Hearn was fascinated by a recurring sense that we are but one step away from a massive precipice, and that we never know truly when we might misstep. In his earliest journalism, which made him famous and notorious, he focused on the underbelly of city life, the marginal spaces that were being suppressed by cities desperate to appear modern and forward-looking — it was here that Hearn sought out the secret gears of urban life, and brought them forth for his readers. Civilization, Hearn understood, could not exist without its uncivilized double, its underbelly that kept the wheels or progress in motion. And Hearn set out to find and write about those places where the veil between these two worlds was the thinnest.

Born in Greece and raised in Ireland, Patrick Lafcadio Hearn came to the United States in 1869, when he was nineteen years old. Penniless, his left eye disfigured from a teenage accident, it was clear, as one friend later put it, “that Fortune and he were scarce on nodding terms.” But his dogged work ethic and the curious charm of his writing style eventually got him a job at the Cincinnati Enquirer, one of the city’s two biggest newspapers. Starting with literary reviews, Hearn quickly caught the attention of the public after a deeply reported story that detailed a shocking murder in the tannery district, a gruesome a lurid mystery in a dingy part of town that most of the Enquirer’s readers had no real notion of. Catapulting to fame on the strength of this piece, he was given more or less carte blanche to write about whatever captured his one good eye.

With a wide and varied curiosity, he sought out the butchers, undertakers and spiritual mediums of the city, reporting on the strange comings and goings of a city bursting at the seams. Ultimately fired from the Enquirer for marrying a biracial woman, he found a job with a rival paper, but eventually headed south to New Orleans, where he remade himself once again. He spent another ten years as a journalist there (interviewing famed Voodoo queen Marie Laveau, among other subjects), before heading to Martinique for a spell and churning out two novels, Chita and Youma.

Along with his stories of murder and mayhem, and his interviews with undertakers and butchers, Hearn built a corpus around that thin line between life and death.

Throughout it all, he was never far from his fascination with the supernatural. Terrified of ghosts as a child, alone at night in his bedroom he would become convinced ghosts were reaching out for him in the dark. He would scream ferociously until an adult would come to check on him, a disturbance that inevitably resulted in being whipped. But, as Hearn would later recall, “the fear of ghosts was greater than the fear of whippings — because I could see the ghosts.” This sense of being surrounded by spirits never left him; and spirit mediums and other ghost stories were a recurrent feature in his journalism. Along with his stories of murder and mayhem, and his interviews with undertakers and butchers, Hearn built a corpus around that thin line between life and death, and our fascination with what lays on the other side.

His first attempt to seriously capture the allure of ghost stories came with his book Some Chinese Ghosts, written in 1887 while he was still living in New Orleans. A lifelong collector of folklore, he’d cobbled together the book primarily from secondary sources; he would later call it the “early work of a man who tried to understand the Far East from books — and couldn’t, but then the real purpose of the stories was only artistic.” It wasn’t until he came to Japan and immersed himself in its culture that he began to forge a style that united his prose with his interest in ghosts and folklore.

*

Five years after a series of well-received articles on the Japanese exhibition at the New Orleans Exposition in 1885, an editor at Harper’s asked him offhandedly if he’d be interested in writing about Japan. Now 40 years old, broke and in need of a change, Hearn jumped at the chance: he relocated to Yokohama, and eventually Tokyo, where he took up a post as Chair of the English Language and Literature department at Tokyo Imperial University.

Supporting himself with a series of travelogues and observations about a country that fascinated Western audiences, Hearn became increasingly fascinated with the country’s ghosts. As the Meiji Restoration rapidly industrialized and modernized Japan, Hearn increasingly turned to out-of-fashion folktales and old stories of Yūrei: unfortunate souls that linger between the worlds of the living and the dead, and who return to torment the living.

Hearn gathered material from old sourcebooks that often contained only incomplete fragments, stories of strange demons and lingering visitations that sometimes made little sense. Having long taught English to make a living, he gradually recruited his stronger students to act as informants for him, gathering up folklore for him.

What would become a hallmark in Hearn’s ghost stories was that omnipresent sense that something was not quite right, even in the telling itself. He instructed his research assistants to “never try to translate a Japanese idiom by an English idiom. That would be no use to me. Simply translate the words exactly, — however funny it seems.” In doing so, Hearn may have helped further the notion of Japanese culture as somehow inscrutable or untranslatable — a not uncommon move by foreigners writing about Japan. But Hearn also managed to tap into something that resonated in his adopted country; Shimane University professor Yasuyuki Kajitani has said that while there have been many foreign authors who’ve written about Japan, “no man of letters before or after Lafcadio Hearn … revealed the beauty of Japan or the Japanese heart, or introduced Japan in such a beautiful style and with such understanding, observation, and deep insight based on a heartful love for Japan’s landscape.”

Help us fund our next story

We’ve published hundreds of original stories, all funded by you — including personal essays, reported features, and reading lists.

In addition to his students, Hearn also turned to his wife. He had married a much younger woman, Setsu, out of convenience — marriage into her family gave him citizenship and legal status, as well as someone to care for him and keep house; in exchange, he was obligated to provide financially for her family. And though he had confessed to a friend at one point that all he wanted in a partner was “some simple, quiet creature who would look after his domestic comfort and stay meekly outside of his realm of thought,” Setsu’s own memoir (published after Hearn’s death) revealed a different relationship altogether. According to Setsu, her husband would ask her to tell ghost stories that she remembered from her youth, always in search of new material. “Hearn would ask questions with bated breath, and would listen to my tales with a terrified air,” she wrote.

When I told him the old tales, I always first gave the plot roughly; and whenever he found an interesting place, he made a note of it. Then he would ask me to give the details, and often to repeat them. If I told him the story by reading it from a book, he would say, “There is no use of your reading it from the book. I prefer your own words and phrases — all from your own thought. Otherwise it won’t do.” Therefore I had to assimilate the story before telling it. That made me dream. He would become so eager when I reached an interesting point of a story! His facial expression would change and his eyes would burn intensely … .

From these dreams and memories he forged some of his most enduring tales — writings that not only resurrected lost folklore in an era of Meiji modernization, but also created fully-fleshed stories out of mere fragments. Among his most famous, “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hōïchi,” tells of the blind musician Hōïchi, approached one night by a stranger who hires him to perform for his lord. Entranced by his music, they instruct him to return each night for a full week. One night, friends discover Hōïchi, alone in a graveyard, singing to the oni-bi, or “ghost-fires,” pale remnants of demons. Realizing he is bewitched, they drag him against his will to a priest who explains that, by once obeying the commands of the dead, he is beholden to them; if he obeys them again, they will tear him to pieces. The priest and his acolyte cover his body with prayers to render him invisible to the demons, but the acolyte forgets Hōïchi’s ears, and when the oni-bi return that night, they can find only Hōïchi’s ears, which they tear from his body, giving him the name Mimi-Nashi-Hōïchi, “Hōïchi the Earless.”

The story of Hōïchi the Earless is one of four tales that director Masaki Kobayashi chose for his 1965 horror anthology film, Kwaidan — a film based not on the original Yūrei stories but Hearn’s retellings. It is a testament to the power of Hearn’s writings that this foreign-born writer has earned a place in the canon of Japanese literature — his work is still celebrated in Japan to this day.

This celebration of Hearn is not uncomplicated: scholar Rie Kido Askew has traced the various iterations of Hearn’s reception in Japanese culture over the past 100 years and suggests that he is often held up as a critique against Japan’s rapid modernization. As a character in Uchida Yasuo’s 1991 book Kaiden no Michi argues, Hearn, “though a foreigner, seems to have understood the proto-scenery of Japan and the subtle parts of the Japanese spiritual structure better than the Japanese. We can indeed learn from Yakumo’s works about the ‘heart’ of the Japanese that [modern] Japanese have forgotten.” Askew argues that Hearn is often evoked “as a symbol to restore the ‘true’ Japan — the simple and innocent pre-modern Japan which … was lost in the process of modernization.” But regardless, it remains the case that for many native readers, when they imagine the ghosts of their culture, it is Hearn’s versions that come to mind.

*

Like Hōïchi, Hearn himself often worked like an artist bewitched. His effortless style and his command of a storyteller’s art — the assuredness of his prose, the careful construction of suspense and mood — all stand at odds to the unsettled nature of many of these stories. A good many horror stories are, at their roots, simple morality tales. The promiscuous, drunk teenagers get serial murdered; the greedy rich man comes to a bad, ironic end. Such stories can be horrific, but they are ultimately reassuring — they present a rigid moral order, even if maintained in gruesome ways. The truly terrifying tales are the ones that follow a logic beyond our grasp, and Hearn’s best ghost stories lie in this strange abyss — the same abyss that we are perpetually and delicately suspended above.

Take “The Sympathy of Benten”: a young poet named Baishū is visiting a shrine of the goddess Benten when a sudden gust of wind blows a long strip of paper towards him, on which a poem about love has been written. Baishū is entranced by the calligraphy on the scroll, imagining the young, beautiful woman who must have written it, and prays to Benten that he might be allowed to meet this writer. His prayer is answered, and, through the intercession of the Old-Man-Under-the Moon, the god of marriage, a young woman appears — the writer of the poem — and they are soon married.

As the Meiji Restoration rapidly industrialized and modernized Japan, Hearn increasingly turned to out-of-fashion folktales and old stories of Yūrei: unfortunate souls … who return to torment the living.

Baishū’s new wife does not talk about her past or her family, and he does not ask, afraid of angering the gods who bequeathed him this gift. “But,” Hearn continues, “neither the Old-Man-Under-the Moon nor any one else came — as he had feared — to take her away. Nobody even made inquiries about her. And the neighbors, for some undiscoverable reason, acted as if totally unaware of her presence.”

Some time later, Baishū is walking through a remote quarter of the city when he is summoned by a stranger, who confesses that he is acting under “an inspiration from the Goddess Benten.” This man has a young daughter who is a talented calligrapher, for whom he has sought a husband; Benten had come to him in a dream the night before predicting the arrival of Baishū, who is to be her husband. The man’s daughter, of course, is identical to the woman Baishū had already married: “She to whom he had been introduced by the Old-Man-Under-the-Moon, was only the soul of the beloved. She to whom he was now wedded, in her father’s house, was the body. Benten had wrought this miracle for the sake of her worshippers.”

This is the end of the tale, but not of Hearn’s telling, as he goes on: “The ending is rather unsatisfactory. One would like to know something about the mental experiences of the real maiden during the married life of her phantom. One would also like to know what became of the phantom, — whether it continued to lead an independent existence; whether it waited patiently for the return of its husband; whether it paid a visit to the real bride. And the book says nothing about these things.” He then quotes a Japanese friend who suggests that something of the girl’s spirit had flowed into the writing, and thus that the “spirit-bride was really formed out of the tanazaku.” Which explains some things, but not others, and doesn’t really get at Hearn’s original questions. The tale is told exclusively from the perspective of the Baishū, so it doesn’t concern itself with the real woman during the phantom maiden’s appearance, or the phantom’s life after the real woman appears. But Hearn is right: the echoes of these other lives ricochet into the main story, leaving unanswered questions.

Stranger still is “The Corpse-Rider,” which first appeared in Hearn’s idiosyncratic collection, Shadowings. “The body was cold as ice,” Hearn begins; “the heart had long ceased to beat: yet there were no other signs of death. Nobody even spoke of burying the woman.” Having died in anger, the townspeople fear that the dying wish of such a person can lead the corpse to “burst asunder any tomb and rift the heaviest graveyard stone.” So her body is left there, as the people wait for the man she was waiting for: the man who divorced her.

The hapless ex-husband soon returns home, and discovers the situation, terrified. “If I can find no help before dark,” he thinks to himself, “she will tear me to pieces.” So he seeks out the help of a Inyōshi, a holy man, who agrees to help him. He leads the ex-husband to the corpse, which is lying face down, undisturbed, and instructs the man to get on the back of the dead woman’s body, like a horse, taking up her long black hair in his hands like a bridle. “You must stay like that till morning,” the inyōshi instructs the man. “You will have reason to be afraid in the night — plenty of reason. But whatever may happen, never let go of her hair. If you let go, — even for one second, — she will tear you into pieces!”

He does as instructed, and the inyōshi leans forward and whispers some magic into the ear of the dead woman, and then tells the man that — for everyone’s safety — he has to depart, leaving the man astride the corpse of his ex-wife. For hours he sit upon the corpse of his dead wife, as the night turns black and strange around him. Then, without warning, the body springs to life, rising up as if to cast him off, the dead woman crying out, “Oh, how heavy it is! Yet I shall bring that fellow here now!” Reanimated, the she leads him on a horrifying night journey:

Then tall she rose, and leaped to the doors, and flung them open, and rushed into the night, — always bearing the weight of the man. But he, shutting his eyes, kept his hands twisted in her long hair, — tightly, tightly, — though fearing with such a fear that he could not even moan. How far she went, he never knew. He saw nothing: he heard only the sound of her naked feet in the dark, — picha-picha, picha-picha, — and the hiss of her breathing as she ran.

At last she turned, and ran back into the house, and lay down upon the floor exactly as at first. Under the man she panted and moaned till the cocks began to crow. Thereafter she lay still.

When the inyōshi returns at sunrise, he’s surprised that the man has lasted the night, and that he never let go of her hair. “But the man, with chattering teeth, sat upon her until the inyōshi came at sunrise. Pleased, he tells him, “That is well … Now you can stand up … You must have passed a fearful night; but nothing else could have saved you. Hereafter you may feel secure from her vengeance.”

So that, more or less, is the end of the story. But Hearn adds a small endnote in which he confesses that he does not find the conclusion of this story to be “morally satisfying.” He complains: “It is not recorded that the corpse-rider became insane, or that his hair turned white: we are told only that ‘he worshipped the inyōshi with tears of gratitude.’”

Hearn’s feeling of dissatisfaction with these tales runs alongside his clear love of the tales himself, and the gusto with which he throws himself into the act of storytelling. He has no answers, only tales. He speaks with a storyteller’s authority, plying all his trade from years of being a journalist, novelist, translator, and folklorist. But what gives Hearn’s yūrei their strange aura, their sense of discomfort is his own uncertainty about the stories he’s telling. In Hearn’s tales, the eerie landscape is the voice of the storyteller itself — it moves under its own power, guided by some unknown and unseen motivation.

Hearn, like his corpse rider, can do more than hold on for dear life.

* * *

Colin Dickey is the author of Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, along with two other books of nonfiction. He is currently writing a book on conspiracy theories and other delusions, The Unidentified, forthcoming in 2020.

Editor: Dana Snitzky

Get the Longreads Weekly Email

Get the Longreads Weekly Email