Katya Cengel | The Atavist Magazine |November 2023 | 1,709 words (6 minutes)

This is an excerpt from issue no. 145, “The Truth Is Out There.”

Bruce Champagne stood in a small clearing next to a stump. It was mid-November 2022, and snow was already visible on the nearby mountains. All around Bruce were stands of reeds known as phragmites, some so tall they reached well over his head. Just a short walk away, through a swampy area, was the western edge of Utah Lake.

Bruce, a retired cop in his sixties, had come to this no-man’s-land to research a mysterious sighting. A few years back, an elderly couple living in a house on a nearby bluff saw something they couldn’t explain. The couple refused to recount their experience over the phone, so Bruce visited them at their home in Saratoga Springs, about 30 miles south of Salt Lake City. They told him that they went into the backyard one day because their dog was barking. Not far away, near a stump in the field behind the house, they saw a figure. A creature.

The Atavist Magazine, our sister site, publishes one deeply reported, elegantly designed story each month. Support The Atavist by becoming a member.

It appeared to be six or seven feet tall. It was dark, hairy, and humanlike. The creature stood up, paused, then walked away, disappearing into the reeds. The whole thing lasted three or four seconds.

After he heard the couple’s account, Bruce measured the distance between the backyard and the stump. It was 60 yards, a range at which, Bruce knew, the couple would have been able to see the contrasting shades of clothing or skin. But they said that the creature was uniform in color. Bruce also noted that it was May when the sighting happened, which is when carp spawn in Utah Lake. Perhaps the animal, whatever it was, had been feeding.

Now Bruce was weighing whether it was worth placing game cameras in the area. He’d installed them at dozens of sites over the previous decade; a blue dot marked each location on a map on his computer. He told me that retrieving data from the cameras, usually after 30 days or so, felt like Christmas morning. Except in this metaphor, Bruce’s gifts always turned out to be socks and underwear. He spent a lot of time watching footage of deer and squirrels, because the cameras never caught what he was looking for: the relict hominoid Sasquatch, popularly known as Bigfoot.

Bruce considers himself a cryptozoologist, someone who searches for and studies animals whose very existence is disputed. Unlike some of the more eccentric types in the field, Bruce is organized and methodical. He has published papers every bit as dry as those in other areas of study—they just happen to be about relict hominoids, sea serpents, and lake monsters.

His specific obsession with Bigfoot began when he was a kid, more than 50 years ago. In fact, it was right around the time his father disappeared. Bruce is reluctant to allow that the two things might be connected, but it’s hard to see it any other way.

Bruce hasn’t looked for the truth about what happened with his father nearly as hard as he’s looked for Bigfoot. Still, the truth keeps finding him and his family. Over the past five decades, revelations about a man who left home one day and never came back have taken Bruce and the rest of the Champagnes by surprise—again and again and again.

1.

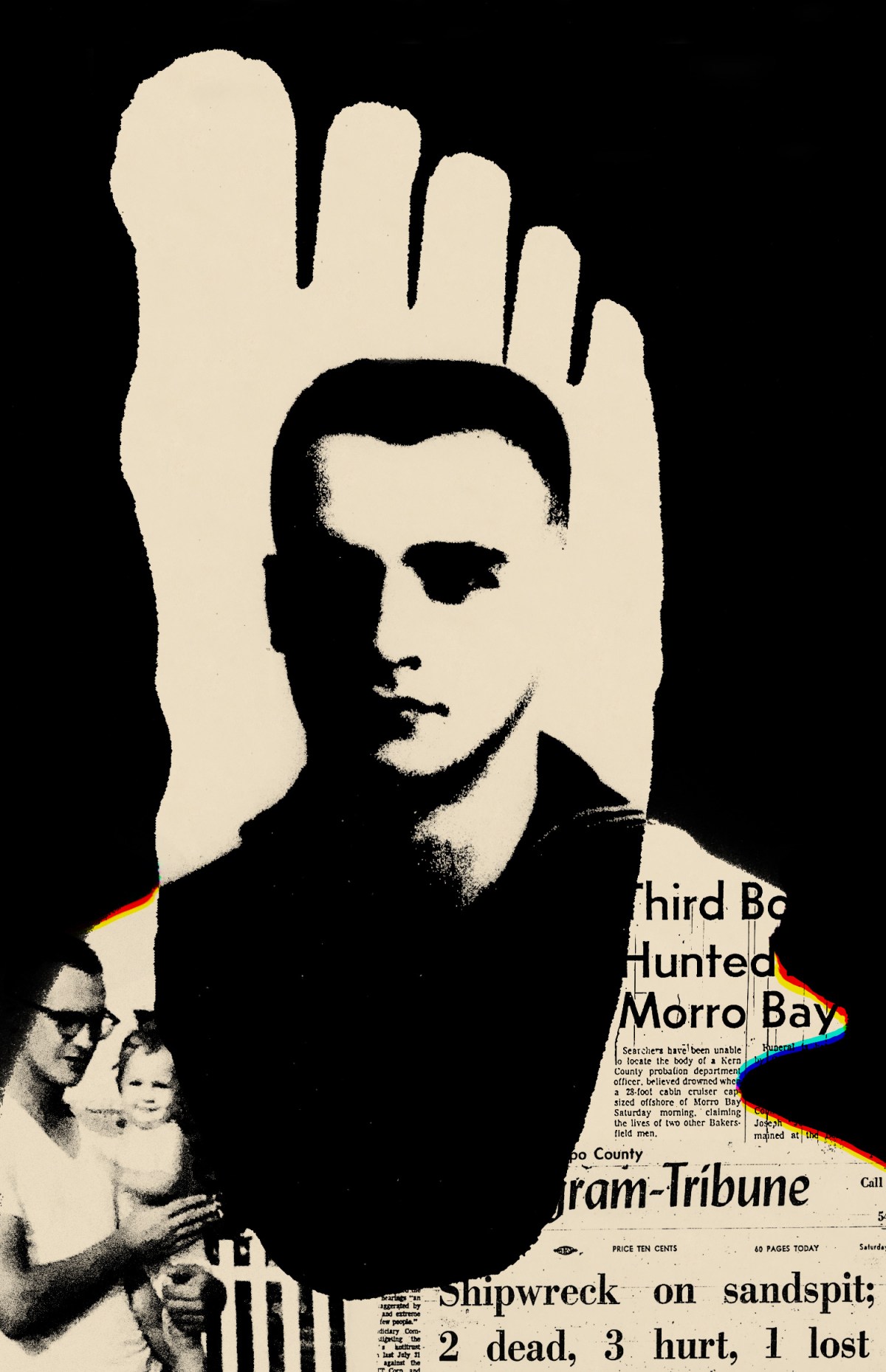

Bruce’s parents met in the Navy. Alan Champagne, the oldest of five from an East Coast family, joined up right out of high school. Lynn Marie Brown enlisted after a brief stint in college studying art. An eccentric young woman who loved science fiction, especially Ray Bradbury, Lynn was 19 when the couple married. After several more years in the Navy, including a posting in Japan, Alan and Lynn settled in Bakersfield, California, a sprawling city of oil wells and orchards populated by the descendants of dust bowl migrants. It was where Lynn had grown up.

Alan found work in the communications sector and then as a probation officer. He attended and graduated from college while working. Lynn took care of the children. There were four boys—Bruce, Brad, Brian, and Barry—and one girl, Deirdre, whom everyone called DeeDee. The boys all had the same middle name: Alan.

Bruce was the oldest. His dad took him shooting, and Bruce used his father’s Winchester 12-gauge. Once when they went fishing at a bass pond, Alan oared out in a rowboat to dislodge a fish his son had caught when it became tangled in some underwater weeds. He could have cut the line, but Alan wanted to make sure Bruce saw the fish he’d caught.

Alan also liked to fish in the ocean. Bruce didn’t go on longer fishing trips, like the one his father scheduled in the late winter of 1972. On Friday, March 10, Alan drove two and a half hours from Bakersfield to Morro Bay, a small community about halfway between San Francisco and Los Angeles. He was meeting a group of friends who worked in law enforcement; they would be gone for the weekend.

Morro Bay got its name from the 576-foot volcanic plug sitting at the mouth of the narrow channel connecting the bay to the Pacific—morro means “snout” in Spanish. The harbor, completed in the 1940s, was a popular launch point for recreational fishing and boating. But there were times, especially in winter, when big swells made navigating the foggy channel treacherous.

According to the Morro Bay Harbor Patrol logbook, word that Alan’s fishing trip was in trouble reached shore at 8:30 a.m. on Saturday. Someone reported that they’d heard a voice calling out for help from a sandspit stretching like a spindly finger up the bay’s western edge. The voice belonged to 15-year-old Steven Stranathan. The boat he was on that morning had capsized.

Steve had been excited to embark on his first fishing trip with a group he called “the guys.” It included Steve’s stepdad, Jack Stranathan, 58, a deputy sheriff and veteran of the Navy and Coast Guard; Joseph Boydstone, 64, a doctor at a Bakersfield jail; and Harry Morlan, 58, and Irlan Warren, 39, both probation officers like Alan, who at 32 was the youngest of the adults aboard.

Steve would later remember kneeling next to Alan just before the accident happened. They were on the cabin deck of a boxy, 28-foot leisure craft made by a company called Land N’ Sea. It was part boat, part travel trailer. It belonged to Jack, who was down below steering. The vessel was more than a mile south of the entrance to Morro Bay and a few hundred yards from the sandspit. The seas were rough. As the boat battled the waves, Steve joked to Alan, “Well, if we go, at least we’ll go laughing.”

The next thing Steve knew it was dark. The boat had split in two and capsized, and he was in the water trying to swim. The cowboy boots his stepdad had mocked him for wearing on the boat were dragging him down. Steve kicked them off, then wriggled out of his Levi’s, flannel shirt, and parka—everything but his underwear. He swam toward the surface. The water got brighter, then brighter still. Steve wondered if he’d make it. Just as he felt sure his lungs would explode, his head burst out of the water.

Steve saw his stepfather floating lifeless nearby. He also saw Harry Morlan clinging to the engines at the stern of the overturned hull. Steve and Harry managed to swim to the sandspit, where another body had washed up: It was Joseph Boydstone. Steve dragged him from the surf.

Soon a Harbor Patrol boat arrived. By 9 a.m. the Coast Guard cutter Cape Hedge was conducting a shoreline search of a five-mile area. Rescue personnel found debris from the boat: two fenders, a canopy. Irlan Warren was also found, alive. Irlan said that after being flung into the water, he swam to the surface. Sometime later, he was able to grab the boat’s propeller shaft and wait for rescue.

The only man unaccounted for was Alan.

At 10:57, an Army helicopter was dispatched to the scene, followed by one from the Navy. By 11:05, a Coast Guard plane had arrived. The pilots made low passes along the ocean side of the sandspit but found nothing.

Meanwhile a dozen firefighters and harbor patrolmen headed toward the white and yellow hull, which by then had beached. Scattered among the driftwood and kelp on the sand were ripped sections of fiberglass, a yellow seat cushion, and a paper plate. Using axes, a crowbar, and a power saw, the men cut a hole in what Land N’ Sea claimed was a “virtually unsinkable” boat. Someone reached into the boat’s cabin and pulled out a leather sandal and a gray plastic box. The crew shone a flashlight inside but couldn’t get a clear view. A rescuer was lowered headfirst into an opening, but if Alan’s body was inside he couldn’t see it.

The Navy tried to flip the hull upright. A rope was slipped under the bow and the other end was attached to a chopper. Three times an attempt was made to lift the wreckage, without success. Shovels came out, and men loosened the sand around the hull. On the fourth try, the helicopter was able to lift the hull and then slam it back down, right side up.

It was now 12:40. The tide was coming in, the ocean lapping at the men’s ankles. From the hull they pulled a waterlogged suitcase, a pillow, and a dented teakettle. Scouring the beach once more, they found a sleeping bag and a tabletop. But there was no body.

There never would be. Which was strange.

“We do have probably a disproportionate amount of accidents out here just because the coast is rough,” said Eric Endersby, who recently retired as director of the Morro Bay Harbor Patrol. Endersby didn’t work the 1972 rescue, but he knows the history of the bay as well as anyone. He said that boating accidents resulting in death are rare. But what’s even more unusual is someone disappearing after a wreck. “If somebody’s lost in the surf, even if they sink, they eventually wash in just because all the wave energy pushes them,” Eric said.

“In my thirty years,” he continued, “we’ve never not recovered somebody.”

Get the Longreads Weekly Email

Get the Longreads Weekly Email