Colin Dickey | Longreads | August 2017 | 14 minutes | 3380 words

We had come to a place muted of light. Every day felt like a potential backsliding, the news unrelenting, as though the nation had finally given up pushing back against its own savagery — and every day felt like the held breath before the fall. I thought increasingly of Stefan Lux, a Jewish journalist from Slovakia: Aghast at the rise of anti-Semitism during the 1930s, and at the inability of Europe’s bureaucratic governments to respond, Lux walked into the General Assembly of the League of Nations and, before the gathered diplomats, fatally shot himself. His last words were “C’est le dernier coup.” This is the final blow. It was only July 3, 1936; the blows would keep coming long after Lux’s death.

The center was not holding; there hadn’t been any center for decades. It was a country of bankrupt politicians, of killings by police so commonplace they barely made the news. It was a country in which families were routinely broken up by early morning immigration raids, where men abducted for traffic violations and women arrested for misdemeanors were sent off to countries they hadn’t known for decades. It was a nation where young white men found solace drifting through rage and irony, and felt alive only by terrorizing others. It was not a country in open revolution, but more and more its people felt revolution would at least be the exhalation they’d been waiting for. It was a country waiting for the final blow.

Whatever rough beast Yeats had seen had already slouched its way out of the desert, laying waste to everything that fell under its pitiless, blank gaze. The body of a lion and the head of a man, the indignant desert birds circling around its slow thighs, it has laid waste to the veneer of civility and decorum that had once been papered over the country.

The sphinx comes speaking of horrors and monstrosities: What is it that walks on four legs, then two, then three? Again and again, no one has an answer for the sphinx’s riddle; no one can imagine something so strange and mutable — and again and again it devours its victims when they fail. Only Oedipus sees that the answer is a human and not some strange creature. Everyone before him has failed to recognize his or her own humanity in the riddle; only Oedipus sees himself in it.

For decades, America has relied on subtext and dog whistle, and in all that time the sphinx has laid waste to us. Now we see ourselves — and now, like Oedipus, our problems are just beginning. It has become easy to look at the wreckage and imagine it only getting worse, and because little else seemed relevant I decided to go to Mount Auburn Cemetery, just outside Boston, to see the sphinx.

***

In May, the city of New Orleans tore down four monuments to the Confederacy: an obelisk honoring the Crescent City White League, long a rallying point for Klansmen and white supremacists; a statue of P. G. T. Beauregard on a horse; a statue of Jefferson Davis; and a bronze statue of Robert E. Lee. “These statues are not just stone and metal,” the city’s mayor, Mitch Landrieu, said. “They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. . . . After the Civil War, these statues were a part of that terrorism as much as a burning cross on someone’s lawn; they were erected purposefully to send a strong message to all who walked in their shadows about who was still in charge in this city.”

Landrieu’s words had a ringing finality to them, even though his speech was far from the final blow. As I drove up from New York City towards Cambridge, I listened to talk-radio pundits commend the great Robert E. Lee, a figure who deserved respect and reverence, they claimed, and whose statues, they felt, ought to be left standing. Their arguments bore the hallmarks of empty ritual; they were clichés that had been espoused for decades without conviction or meaning.

Monuments in America have always embodied a fraught paradox: They are meant to seem as though they’re merely reflecting the past, instead of shaping it. “Monuments attempt to mold a landscape of collective memory, to conserve what is worth remembering and discard the rest,” writes Kirk Savage in his history of post–Civil War monuments, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America. They appear to arise out of thin air, a popular and acclaimed expression of the people, when in fact their design and creation are deliberate political acts. As Landrieu told the city of New Orleans, “There are no slave-ship monuments, no prominent markers on public land to remember the lynchings or the slave blocks, nothing to remember this long chapter of our lives: the pain, the sacrifice, the shame . . . all of it happening on the soil of New Orleans.”

As I listened to the voices on the radio, I realized that to be white in America is to constantly forget, to live in a permanent fog. There is no way to contain the promises of equality with the realities you see before you. You cling to amnesia; you forget the details of slavery, of Jim Crow, of the civil rights movement. They could have equality if they wanted it, you tell yourself, if they worked for it instead of complaining. When you believe such lies, you look to the statues of Robert E. Lee. The general, who broke up nearly every slave family on his Arlington estate, was whitewashed as an apolitical soldier, a gentleman hero of a depoliticized South. No figure embodies our national amnesia like Lee, resplendent in marble astride his horse Traveller, whose name is known by every white Southerner despite its meaninglessness.

Winding my way through the rural highways of upstate New York, past houses still adorned with Confederate flags, I thought of a story I’d read recently involving Lee’s horse. While raising money for a statue of the general in Richmond, Virginia, boosters spread the story that in 1871 Traveller had refused to allow a young black boy to mount him — an apocryphal piece of propaganda meant to suggest that the horse, as all of nature must, understood the superiority of the white man. Enlisting a horse as a symbol of racism spoke to a particularly dark impulse in our country’s humanity, and Lee has become so inextricably linked to his horse that the pair seemed to have fused in statues around the country, a centaur standing once and for all for the stain of American slavery.

Heading east along the turnpike in Massachusetts, I passed a giant quarry just off the freeway, a gouged-out wound in the earth from which, no doubt, the raw material of many of these statues was birthed — plunging down into the depths, these quarries, the scars of which will long outlast even our greatest architecture, are perhaps a more fitting monument to human history. The statues created by the North are not without their problems either. Looking to commemorate emancipation, abolitionists and white Northerners could never easily reconcile the body of a freed slave with their inherited tradition of classical statues and monuments. Whites could envision the body of the enslaved American only as scarred, broken, and humiliated.

Instead, Northerners commemorated the war and abolition with statues of Abraham Lincoln: Often alone, holding a pen to symbolize the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation — or in the case of Thomas Ball’s garish statue near the National Mall, standing over a subservient freedman, debased beneath his white savior. Commemorative monuments portrayed anonymous Union soldiers — cheap, mass-produced statues made with molds identical to those used in the South for Confederates. Writing in The Atlantic Monthly in 1866, William Dean Howells warned of filling our parks and cemeteries with “bas-reliefs of battles, and statues of captains, and groups of privates.” But multiple Lincolns, along with the nameless white privates of the Union army, rose up, a ghost army in bronze, erasing America’s black population in the North as it had in the South.

[pullquote align=”center”]Looking to commemorate emancipation, white Northerners could never easily reconcile the body of a freed slave with their tradition of classical monuments. Whites could envision the body of the enslaved American only as scarred, broken, and humiliated.[/pullquote]

As I arrived at Mount Auburn there was a funeral service at the main chapel by the entrance. Not wanting to interrupt, I began a slow, ambling drive around the perimeter of the cemetery, assuming that I would be able to chance upon the statue eventually. In these lazy concentric circles I worked my way toward the middle of the cemetery, a gradual spiral that took me finally to a rising hill in the center of Mount Auburn, where I found the great Sphinx.

The giant block of granite quarried from Maine exerts its own gravitational pull, dominating the landscape even as it is partly shrouded by maple boughs. The Sphinx wears an American military medallion; its headdress is crowned with the head of a bald eagle. On the southern end of the pedestal is an Egyptian lotus, while the northern end features an American water lily. Other than the medallion, there’s little indication it’s a war memorial, aside from an inscription on its base, in both Latin and English: American union preserved, American slavery destroyed, by the uprising of a great people, by the blood of fallen heroes.

***

The Sphinx was the vision of Dr. Jacob Bigelow, a Harvard botanist and physician who was one of the founders of Mount Auburn Cemetery. In the wake of the Civil War, he wanted a monument that would honor the sacrifices of the Union army and point the way toward a more integrated America. A figure from Egyptian mythology, the sphinx represents the fusion of both “American” and “African” motifs, a perfect union between black and white.

Bigelow had dreamed up the statue and designed it entirely himself. Egyptian motifs had associated in nineteenth-century America with mourning and grief, but these had never included a sphinx. Bigelow’s monument was to be his own, ex nihilo and sui generis. Bigelow’s dreams swam with hybrid monsters. The Elgin Marbles, he noted, “to which the whole world pays homage,” consist of depictions of centaurs and other strange creatures; and the winged steed Pegasus, “on which poets in all ages have sought recreation,” was also an amalgamation of different beasts. “Even angels,” he concluded, “the accepted embodiments of beauty and loveliness, are human figures with birds’ wings attached to their shoulders.” Why, then, not revere another hybrid, why not create a new mythology?

Bigelow tried to envision a nation beating its swords back into plowshares, commending “a great, warlike, and successful nation, in the plenitude and full consciousness of its power, suddenly reversing its energies, and calling back its military veterans from bloodshed and victory to resume its still familiar arts of peace and good-will to man.” Believing that the final blow had at last been struck, he asked, “What symbol can better express the attributes of a just, calm, and dignified self-reliance than one which combines power with attractiveness, the strength of the lion with the beauty and benignity of woman?”

Bigelow enlisted sculptor Martin Milmore to craft his legacy, and the sculpture bears both Bigelow’s and Milmore’s names on its pedestal. Rather than Lincoln and an emancipated slave, Bigelow made the African component symbolic, attempting to establish a language of aesthetic beauty and still indicate Africanness — as though he might give white America an oblique lens by which to glimpse the black body. In envisioning a hybrid featuring a white, Anglicized face and the body of an African animal, Bigelow re-created a standard American racism, under which the “African” part of America could be expected to do physical labor, guided by the “intellect” and “beauty” of the white head. It is dismaying that, for all his originality, Bigelow could not see beyond this blind spot, so that despite the grandeur of Milmore’s work, what remains striking about the Sphinx is that it is composed of insufficient half measures, an aesthetic that fails on its own merits.

Bigelow’s Sphinx is far from perfect, far from above reproach. But if it has a saving grace, it is the strangeness of this nearly illegible beast. While Bigelow was alive, he could explain the statue, put it into context for onlookers and critics. With his death the Sphinx began to change. Visitors to Mount Auburn gradually became less confident about the purpose of the statue. It was still imposing, still a work of singular art, but its meaning began to elude those who met its placid gaze. The inscription did little to remind visitors of the Sphinx’s purpose. Rather than representing Bigelow’s vision of a united America, more and more visitors saw the enigmatic destroyer of Greek myth.

Charlotte Fiske Bates’s 1879 poem “The Sphinx at Mount Auburn” recasts Bigelow’s masterpiece as the tormentor of Thebes:

How grand she is enthroned among the dead,

The graves like trophies all about her spread!

Have these not perished as in fable old

With some unfathomed riddle in their hold?

In one of the few scholarly articles on the Sphinx, historian Joy M. Giguere writes that most Civil War monuments have endured because of

the sheer repetition of their designs over the cultural landscape. The creation of similarly-styled monuments, whose designs were agreed upon by monument committees or memorial associations, conveyed a broad cultural consensus as to what the war’s significance and legacy entailed.

But those same monuments — even those in the North — also maintained a racial separation, portraying “the heroism of white soldiers, the appreciation of emancipated slaves, but never the kind of racial cooperation or fusion expressed by Bigelow’s Sphinx.”

A strange outlier without an immediate referent, the Sphinx would become obscure within a few decades. In 1905, the Presbyterian minister Daniel Edward Lorenz spoke for many when he confessed his confusion and horror about it.

Was it erected in ignorance of its meaning? Or was it an intentional insult to all our fondest hopes? Does it mean that death is like that Greek monster? What does it mean? In the Necropolis of a pagan people, to whom life and immortality had never been brought to light, that statue might not surprise us, but what right has it to cumber the ground in the burial place of a Christian people?

Bigelow’s vision had quickly become inscrutable, and while visitors still heaped praise upon Milmore’s artistic genius, the work itself remained misunderstood.

As I spent the late morning and midday in the cemetery with Bigelow’s great Sphinx, I too gradually felt I could no longer make sense of it — the meaning of the statue, once clear to me, grew more and more inscrutable the longer I gazed at its empty stare.

***

Riding a wave of acclaim on the back of the Sphinx, Martin Milmore seemed poised to reshape the entire landscape of the city of Boston. Born in Ireland in 1844, Milmore came to Boston in 1851 and within ten years was already a rising star. Educated as a stonecutter by his older brother Joseph, the teenage Martin was taken on as an apprentice by Thomas Ball. Reports quickly emerged of an “unusually fine talent” in Ball’s studio, a young man whose artistry was quickly outstripping his peers’. Ball recommended his pupil for a significant commission: three allegorical statues for the Boston Horticultural Hall. Depicting three Roman goddesses of agriculture (Ceres, Pomona, and Flora), the statues’ success enabled Milmore to open up his own studio. Within a few years of the horticultural allegories he was sculpting marble busts of Massachusetts’s luminaries: Longfellow, Emerson, and the abolitionist Charles Sumner among them. In 1877, after the success of the Sphinx, Milmore completed his most well-known work: Boston’s Soldiers and Sailors Monument — the only official monument in the city proper honoring Boston citizens who’d died in the Civil War.

The only thing stopping Milmore was his own health: Cirrhosis of the liver killed him at the tragically young age of thirty-eight, and with his death the meaning of the Sphinx would fade behind yet another layer. After Milmore died, Daniel Chester French carved a funerary monument to him, which would in time be erected on the other side of the city, at Forest Hills Cemetery.

While it had been sunny and clear that morning, by afternoon a diffused gloom had set in, compounded by the grim crosstown commute through Boston’s labyrinthine streets, meaning that I arrived at Forest Hills tense and anxious, and it took a moment, sitting in an idling car at the gates, to recompose myself. As a local friend told me later, while Mount Auburn is best experienced on a bright, warm day, Forest Hills is best seen amid the gloom; somehow on this front the weather had participated beautifully. And after a few turns through avenues all named for trees — Maple, White Oak, Linden — I returned back to the gates, only to see the monument almost directly in front of me.

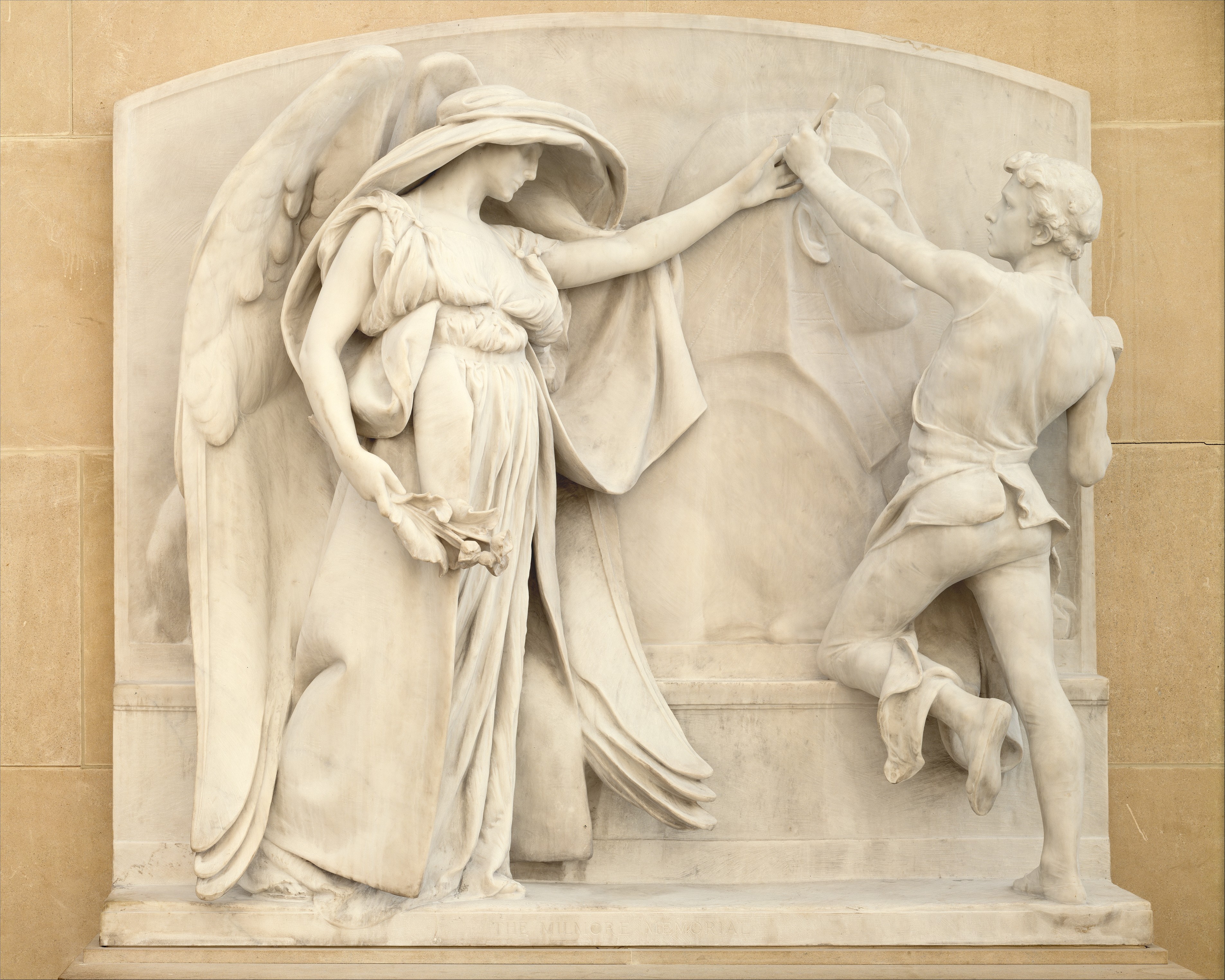

French’s memorial display is of a youthful sculptor — said to be Milmore, but evoking more a cherub than an adult artist — working on his creation, a chisel in his left hand and a mallet in his right. As his right hand raises the mallet to strike another blow, his left hand is stopped by the robed personification of death, her face heavily obscured by folds of a hood. Because of the sharp delineations of the sculptor and Death, it can be difficult at first to see what the sculptor is working on — particularly in the sculpture’s original bronze, the object of his toil recedes into darkness, but as you approach the relief it becomes clear that there is a fading third figure of this drama: the Sphinx.

While the Sphinx perches atop a central hill in Mount Auburn, French’s sculpture lies at a remove, at the far end of a small lawn. He implies that Death has interrupted Milmore’s work on the Sphinx, that the latter is somehow incomplete — a nod, perhaps, to the fact that even by then its meaning had grown ambiguous.

French would later make several copies of his monument in marble, including one that ended up in Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exhibition, a work that inspired the poet Horace Spencer Fiske to write,

O Death thou canst not touch him thus apace

With thy remorseless, petrifying hand!

For e’en already at his sweet command

The Sphinx grows gentler, breathing to the race

The mystery of life, and all the grace

That crowns it in the fear and shadowed land.

There is another copy in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Well lit in an airy courtyard, the marble reproduction has a clarity the original lacks. Devoid of its original context as a funerary monument, there is little to indicate that it marks either the dead sculptor or the Union troops whom he once himself honored. The American Wing of the Met, after all, is not too far from its Egyptian collection, a proximity that seems to complete the circle, drawing Bigelow’s inspiration back toward this copy of an homage.

Shortly after the museum’s acquisition, Preston Remington noted that the angel of death “is the very embodiment of the static forces of the ages — the Great Mother from whom all energies are given out but to whom also they must ultimately return.” But is this not also true of the Sphinx, which stands behind both figures, watching silently over both Death and humanity? As art critic Royal Cortissoz, would write in the Atlantic Monthly, what French hoped to symbolize “was the curtailment by death of any manly life dedicated to plastic art, and to recall in the Sphinx upon which the sculptor is engaged, not the well-known monster which Milmore himself once produced, but the insoluble mystery which stands forever between life and death.”

***

In the wake of Charlottesville, statues have come down in Baltimore, in Los Angeles, in New York City; they have been torn down in Durham, North Carolina, the metal crumpling after a short fall, a reminder of the cheapness by which they were made. With any luck, they will all come down, either by vote or by force. The problem with sculpture is that it attempts finality. It attempts once and for all to cast our country’s history in stone and bronze and then to let it rest. It resists the realization that there is no final blow, that America’s future lies in its slow and bloody progress. Such monuments to terrible finality must always be distrusted, for a racist country will take any object of permanence and bend it to its ends.

Whatever meaning Bigelow hoped people would take from his opus, the Sphinx calls to me because it is monstrous — it asks a riddle about humanity’s monstrosity that must be answered by each generation anew. To be white in America is to have this obligation. The Sphinx demands that you recognize yourself, as the strange beast of its riddle.

Perhaps this is the only work that remains to be done — to sculpt figures that point to the great tragedy of our country with no promise of hope, to put hammer to chisel, blow after blow, forging monsters that beckon with an endless gaze. To create riddles that cannot be undone, riddles that will outlast us unsolved and echo into future generations. To toil against the stone until Death arrives to still our hand.

***

Colin Dickey is the author of Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, along with two other books of nonfiction. He is also the co-editor of The Morbid Anatomy Anthology.

***

Editor: Michelle Legro

Illustration: Katie Kosma

Fact-checker: Ethan Chiel

Copy-editor: Ryann Liebenthal

Get the Longreads Weekly Email

Get the Longreads Weekly Email